Russian Silver period

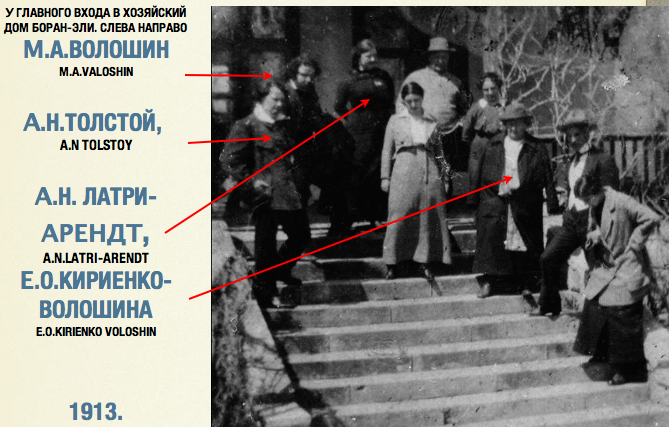

Max Voloshin, shown here, was a poet of the Silver Age. This term, applied to the last decade of the 19th century and first two or three of the 20th century, was an exceptionally creative period. There were many such poets as Ivan Bunin and Marina Tsvetayeva and Alexander Blok. The poetic careers of Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, and Osip Mandelstam, were also launched during this period. The Silver Age ended after the Russian Civil War with Blok’s death and Nikolai Gumilev‘s execution in 1921.

Associated with the Russian magazine World of Art (Мир искусства) it included Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and Sergei Diaghilev, Valentin Serov, Konstantin Korovin, Boris Kustodiev, Zinaida Serebriakova, Ivan Bilibin, Konstantin Somov, Dmitry Mitrohin, Nicholas Roerich & Serge Sudeikin. Artistically it heralded Russian Symbolism and Russian Futurism.

Mikhail Lattry had to escape for his life from the Bolshevik onslaught but many artists remained for the initial flowering of the Russian avant garde imbued with delusional revolutionary hope only to be cruelly betrayed, confirming that revolutions always eat their own children! Lastly Mir iskusstva (Мир искусства) held exhibitions in 1918, 1921, 1922. Ironically, the last exhibition of Mir iskusstva was organized not in Russia, but in Paris in 1927.

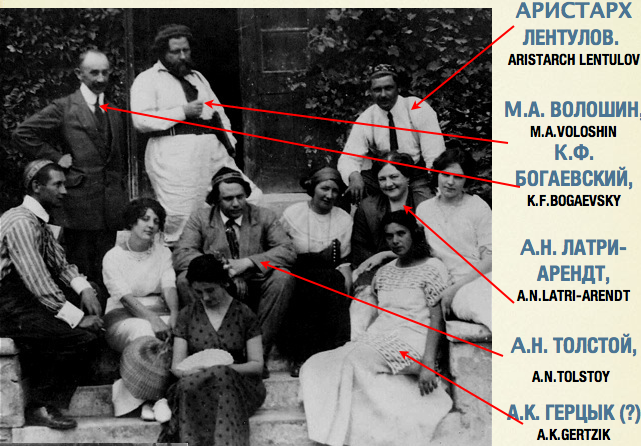

Artists of the Russian ‘Silver Period’ at Boran-Eli, the home of Mikhail Lattry in the Crimea.

Material from the Arendt archive, with kind permission.

From earliest childhood I spent my summers in Boran-Eli (now Kashtanovka) near Stariy Krim where my aunt Ariadne Nikolaevna Lattry lived. Her husband Mikhail Pelopidovich Lattry, the grandson of I.K. Aivazovsky was himself an artist. In the summer Boran-Eli was the gathering place of creative intelligentsia – K.F. Bogaevskiy, M.A. Voloshin, V.P. Belkin, and many others. Ariadna Arendt the younger (Alia).

Lattry had a ceramic workshop, where I continuously observed the miraculous apparition of pots and vases upon the pottery wheel. When I looked into the kiln I saw the ceramic creations, searing almost transparent, of extraordinary beauty, yet when they cooled, covered in their coloured glazes they became even more beautiful. All this for me was like some divine magic, the same as that of painting appearing on a blank canvas.

His decorative ceramics, using local clay, were shown in Isdebsky’s salon in 1909-1910, later becoming important in the transition between the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles. The main collection is in the Aivazovsky Gallery, Feodosia. Ariadna Arendt the younger (Alia).

In Boran Eli the estate of Michael Latri (Ceramics In the Aivazovsky Gallery, Feodosia.)

In the summer, I was usually taken to Boran Eli the estate of my aunt Ariadna Latri, nee Arendt, near the town of Old Crimea. In fact, the estate belonged to her husband, the grandson of the artist Aivazovsky, who had purchased estates for each of his  four daughters in Eastern Crimea, near Feodosia. There I grew and gradually absorbed the love of art. I was a reclusive child, friendly with the common folk and avoided the children of intellectuals, who often came with their parents to Boran Eli. I remember that I once singled out Irina Lampsi, as well as Aivazovsky’s great-granddaughter [Gayane Mikeladze, who was close to Alya in age and grew up in the nearby estate of Krynichky] who was pensive and showed an interest in me, but because of my reclusive shyness, we never made friends despite our mutual sympathy… .. <……..>

four daughters in Eastern Crimea, near Feodosia. There I grew and gradually absorbed the love of art. I was a reclusive child, friendly with the common folk and avoided the children of intellectuals, who often came with their parents to Boran Eli. I remember that I once singled out Irina Lampsi, as well as Aivazovsky’s great-granddaughter [Gayane Mikeladze, who was close to Alya in age and grew up in the nearby estate of Krynichky] who was pensive and showed an interest in me, but because of my reclusive shyness, we never made friends despite our mutual sympathy… .. <……..>

It was in Boran Eli, in childhood, that I felt for the first time a desire to sculpt. The husband of my aunt, Mikhail Pelopidovich Latri (a Greek through his father) was a good painter.

I could watch him working for hours. He also made ceramics, and this especially attracted me. Several people were employed in his ceramic workshop. Misha himself, Kolya Belyaev [it turned out that he was a relative of the wife of Yura Arendt] and two workers: a potter from the Crimean Germans and Martyusha, who prepared the clay, stoked the kiln and took the finished wares to the market in Old Crimea.

Misha had no office or paperwork, except for a notebook and pencil hanging on the wall, where he noted down the figures of expenses and income. There were two small adjacent rooms. In the first room there was a potter’s wheel, on which Martyusha and the potter worked, making clay trinkets: whistles, roosters, pipes and other toys.

The artists worked in the second room, that is Misha himself and Kolya Belyaev. They made different artistic forms: vases and human figures. I remember a Tatar with a basket of fruit, a ridiculous fat Turk intended as a lampstand onto which a lampshade was attached [This figure is now in the permanent collection of the Aivazovsky Gallery].

There were also many different statuettes: monkeys and human figures. I observed the artists at work. Most of all I delighted in seeing how, amorphous lumps of clay on the spinning wheel, would at the master potter’s command transformed into the unusual and perfect forms of vases, pots, and jugs. It seemed to me some kind of magic, and I could watch them for hours.

The German master made little rooster-shaped whistles from clay pats. He placed a pat on his palm, quickly squeezed his hand shaping the rooster’s little body; moistening the fingers of his other hand and running them over this body he stuck together its back, attaching the comb and wattle; then with a wooden chip he made a hole in the right place for the whistle and with the same chip cut a square hole below, and on the side of the same chip he made several holes for a variety of sounds. Such roosters were dried, then fired in the kiln and painted with bright water colors. All this was done with lightning speed. One flat box stood in front of the master where he placed the roosters to dry, in another box were the cockerels ready for painting, already fired.

These wares were loaded into the cart, and the horse carried them to Old Crimea to the bazaar. As was customary in the Crimea all the goods at the bazaar were laid on ground near the Tatar open stalls. The horse was unharnessed and given her grain, which was poured into sacks specially sewn in the shape of a horse’s snout, this “tasty” muzzle was put on the horse. Small leather triangles always hung on the sides of this peculiar feeding-bowl. These were horse amulets. Inside they had a wooden chip with an inscription conducive to the welfare of the horse. I once went to the Old Crimea and admired the Tatar bazaar with interest, where, in addition to pottery, they sold bright fez hats, mens always with a tassle, and womens with gold ornaments. Marama was also sold – embroidered pieces of fine white fabric, which in the Tatar houses played the role of paintings and hung under the omnipresent shelves, fitted along all the walls. After selling almost all our goods, we sat in the cart and drove back to Boran Eli. The coachman, I remember, was called Yakim.

Once, as I stood and admired how the master skilfully crafted these roosters, he suddenly took my hand and placed a clay pat prepared for the next rooster on my open palm. Then he began to squeeze my fingers with his hands, trying to teach me how to make these whistles. I didn’t succeed, and I ran away in annoyance and embarrassment with the piece of clay squashed in my hands, somewhere far into the steppe on the edge of an oat field, hoping to make a bust of Napoleon. I didn’t manage to make Napoleon, and began another rooster. But the clay dried up and cracked, the cockerel also failed me. But having felt the pliability of clay, later in Simferopol I began to gradually sculpt human faces and animal figures in clay.

В имении Михаила Латри Боран Эли

В имении Михаила Латри Боран Эли

Летом меня обычно возили в имение моей тети Ариадны Латри, урожденной Арендт, Боран Эли под старым Крымом. Собственно говоря, имение принадлежало ее мужу, внуку художника Айвазовского, который всем своим четырем дочерям, приобрел по имению в Восточном Крыму, близ Феодосии. Там я росла и постепенно впитывала любовь к искусству. Я была замкнутым ребенком, дружила с простонародьем и почему-то очень чуждалась детей интеллигентов, которые часто приезжали со своими родителями в Боран Эли. Помню, что я как-то выделяла Ирину Лампси, а также правнучку Айвазовского,* Гаянэ Микеладзе, которая была близка к Але по возрасту и росла в соседнем имении Крынички*

которая была задумчивая и интересовалась мной, но в силу моей замкнутости и застенчивости, мы, несмотря на взаимную симпатию, не подружились….

В Боран Эли в детстве впервые у меня зародилось желание лепить. Муж моей тети Михаил Пелопидович Латри (грек по отцу) был хороший художник живописец.

В Боран Эли в детстве впервые у меня зародилось желание лепить. Муж моей тети Михаил Пелопидович Латри (грек по отцу) был хороший художник живописец.

Я подолгу могла смотреть, как он работает. Он занимался еще и керамикой, и это меня особенно привлекало. В его керамической мастерской работало несколько человек. Сам Миша, Коля Беляев* выяснилось что он родственник жены Юры Арендта

и два рабочих: гончар, немец из крымских колонистов и Мартюша, который приготавливал глину, топил горн и отвозил готовые вещи на базар в Старый Крым.

Канцелярии у Миши не было, кроме блокнота, висящего на стене и, также висящего, карандаша, которым и записывались в блокнот необходимые цифры расходов и доходов. Там было две небольшие смежные комнаты. В первой комнате стоял гончарный круг, на котором работали Мартюша и гончар, лепивший глиняные безделушки: свистки, петушки, дудочки и другие игрушки.

Во второй комнате работали художники, то есть сам Миша и Коля Беляев. Они делали разные художественные модели: вазы и человеческие фигуры. Помню татарина с корзиной фруктов, смешного толстого турка,*Эта фигура сейчас находится в постоянной ‘кспозиции в галерее Айвазовского*

- это был остов лампы, на который надевался абажур. Еще было много разных статуэток: обезьянки и человеческие фигурки. Я следила за работой художников. Пожалуй, больше всего мне нравилось смотреть, как на вертящемся круге из аморфной глиняной глыбы по желанию мастера-гончара возникали необычные, совершенные по форме вазы, горшки, кувшины. Мне это казалось каким-то волшебством, и я могла часами им любоваться.

Мастер немец из глиняных лепешек лепил свистульки-петушки. Он клал на ладонь такую лепешку, быстро сжимал ладонь, и получалось тельце петушка; смачивал пальцы другой руки и, водя по этому тельцу, склеивал спину петушка, прилепляя к голове гребень и бородку; затем брал в правую руку деревянную щепку, которой проделывал в нужном месте дырку для свистка и этой же щепкой вырезал квадратное отверстие ниже, сбоку этой же щепкой он проделывал несколько дырочек для разнообразия звуков. Такие петушки высушивались, затем обжигались в горне и раскрашивались яркими водяными красками. Все это делалось молниеносно. Перед мастером стоял плоский ящик, куда он ставил своих петушков сушиться, в другом ящике стояли петушки, готовые к окраске, уже обожженные.

Эта продукция грузилась в мажару, и лошадь везла все это в Старый Крым на базар. На базаре, как это было принято в Крыму, весь товар ставили на землю возле татарских открытых лавочек. Лошадь распрягали и давали ей зерно, которое насыпали в так называемые торбы, специально сшитые по форме лошадиной морды, этот «вкусный» намордник надевали на лошадь. По бокам этой своеобразной миски всегда висели небольшие кожаные треугольники. Это были лошадиные талисманы. Внутри клалась щепка с надписью, благоприятствующей благополучию лошади. Я как-то раз поехала в Старый Крым и с интересом любовалась татарским базаром, где кроме гончарных изделий продавались яркие фески, мужские – обязательно с кисточкой и женские – с золотым орнаментом. Еще продавалась марама – вышитые куски тонкой белой материи, которые в татарских домах играли роль картин и вешались под неизменными полками, укрепленными в комнатах вдоль всех стен. После распродажи почти всего товара мы сели в мажару и поехали обратно в Боран Эли. Кучера, помню, звали Яким.

Как-то, когда я стояла и любовалась, как мастер виртуозно делал петушков, он неожиданно взял мою руку и на раскрытую ладонь положил глиняную лепешку, приготовленную для очередного петушка. Затем своими руками стал сжимать мои пальцы, стараясь научить меня делать эти свистульки. У меня не получалось, и я от досады и смущенья вырвалась и убежала с куском смятой глины в руках, куда-то далеко в степь на край овсяного поля, мечтая вылепить бюст Наполеона. Наполеон у меня не получился, я стала делать петушка. Но глина высохла, растрескалась, петушок тоже мне не удался. Однако, почувствовав ощущение податливой глины, я позже уже в Симферополе стала понемногу лепить из глины человеческие рожицы и фигурки зверьков.